Iris Research and Modern Technology: AI Implications in Iridology

Modern Smartphone Pupillometry: What Automated Collarette Analysis Means for Iridology

The integration of AI-driven collarette analysis into smartphone pupillometry marks a pivotal moment for clinical iridology and autonomic assessment. It connects decades-old cardiovascular research with today’s digital imaging, making iris-based autonomic insights more measurable, repeatable, and accessible than ever before.[1-4]

What Is the Collarette (Autonomic Nerve Wreath) and Why Does It Matter?

The collarette, also known as the autonomic nerve wreath (ANW), is a ring-like structure circling the pupil, typically about one-third of the distance between the pupil border and the outer iris edge. In classical and contemporary iridology, it is considered a major landmark that separates the intestinal zone from the rest of the body’s organ and gland representations.[1,5-7]

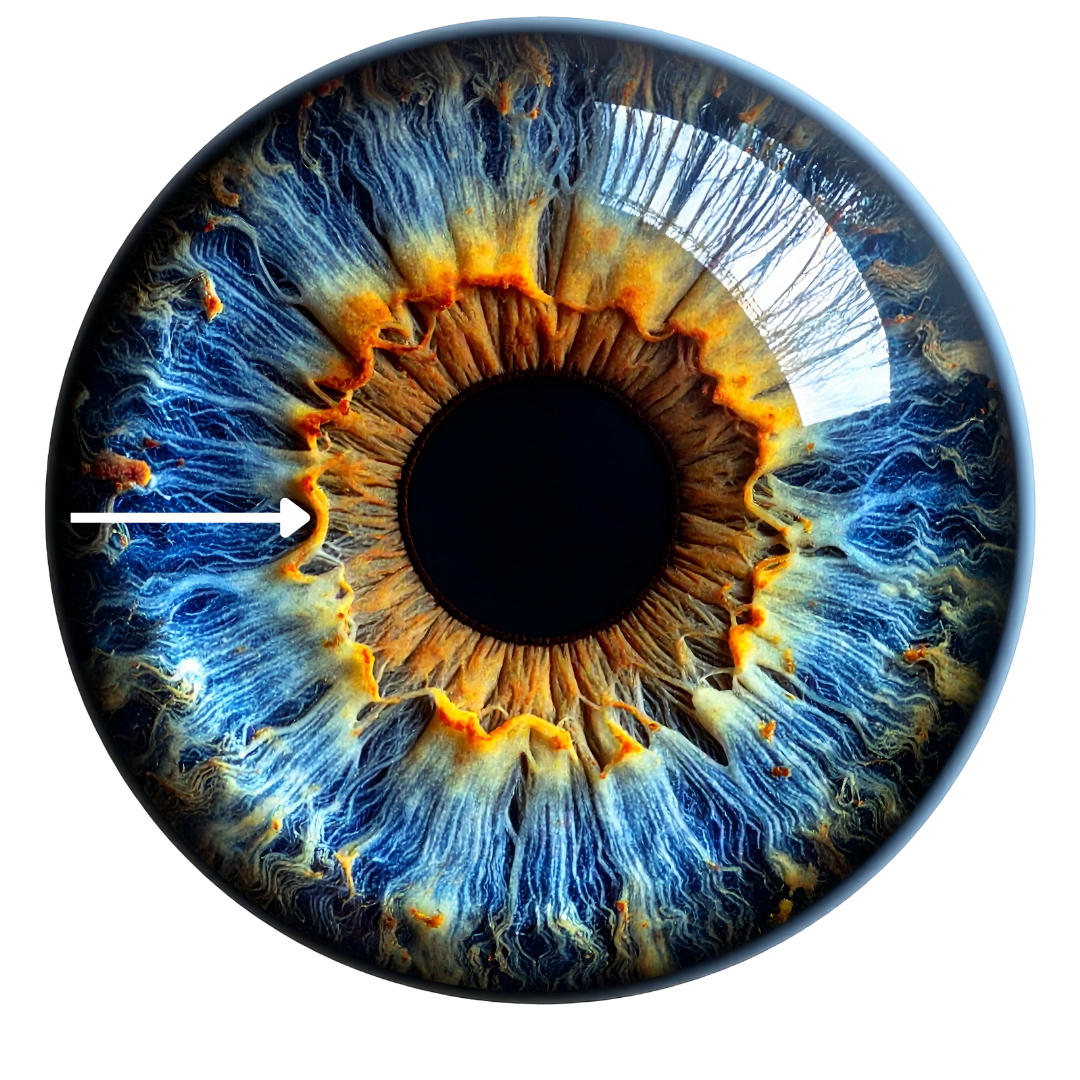

A white arrow showing a prominent, irregular collarette, a clear boundary between the area closest to the pupil to the rest of the iris.

From a physiological perspective:

The collarette overlies a vascular and neuromuscular region associated with the minor arterial circle of the iris and the musculature regulating pupil size and iris tone.

It reflects the interplay between the sympathetic and parasympathetic branches of the autonomic nervous system, acting as a visual marker of autonomic “tone”, adaptability, and visceral reactivity.

Its development completes in early childhood, and structural changes may reflect long-standing autonomic, visceral, or inflammatory influences.

For iridologists and integrative clinicians, this makes the collarette a central feature in interpreting gut–brain axis dynamics, cardiovascular resilience, and overall autonomic balance.

Revisiting Velhover’s Cardiovascular Research on the Collarette

In the mid-1980s, Velhover and colleagues carried out large-scale observational studies on iris morphology in cardiovascular patients, comparing nearly 700 individuals with heart disease to over 200 healthy controls. Their work systematically linked collarette displacement patterns and protrusions to underlying cardiac and haemodynamic changes, particularly:

A baseline rate of collarette bulging in healthy subjects, observed in roughly 9.5–26.3% of individuals depending on sector.

A significantly higher prevalence of collarette bulging in heart patients, especially in the left iris, where protrusion appeared in more than 80% of cases in relevant sectors.

Beyond raw percentages, Velhover’s team suggested that specific sectoral shifts corresponded to:

Left ventricular overload (commonly associated with middle-temporal collarette shift in the left eye).

Inferior vena cava haemodynamic disturbance.

Vagal or stellate ganglion hypofunction.

Pelvic congestion and inflammatory states.

Vertebrobasilar insufficiency (associated with upper temporal shifts)

These correlations highlighted the collarette not as a static line, but as a dynamic morphological structure that appears to respond to long-term cardiovascular and autonomic stressors.

The Collarette as an Autonomic and Gastrointestinal Marker in Iridology

Modern iridology texts and training materials still consider the collarette the “nerve wreath”, describing it as:

A visual expression of sympathetic–parasympathetic union and balance.

A boundary between the intestinal tract and systemic organ fields.

A marker of intestinal tone, bowel transit tendencies, and autonomic resilience or fragility.

Commonly described qualitative patterns include:

Zigzag or toothed collarette: Often associated with hyperreactive gastrointestinal function and mood variability in iridological interpretations.

Hypoplastic (thin) collarette: Linked with delicate autonomic regulation, heightened sensitivity, and lower stress tolerance.

Hyperplastic (thick) collarette: Interpreted as an “irritable” autonomic nervous system with over-reactivity or over-acidity.

Parallel track (double) collarette: Associated with inherited patterns or depressive tendencies in some iridology traditions.

Sectoral absence or rupture: Interpreted as insufficient regulation or severe autonomic/neurological compromise in corresponding body zones.

These qualitative descriptions align with the concept of the collarette as a higher-order autonomic signal rather than a purely geometric feature.

Rise of Smartphone Pupillometry and AI in Autonomic Assessment

Parallel to developments in iridology, mainstream research has rapidly advanced smartphone-based pupillometry. Several groups have now validated mobile apps that:

Use standard smartphone cameras or near-infrared sensors to measure pupil diameter and dynamics with sub-millimetre precision.

Achieve error margins as low as 0.27 mm in pupil size compared to gold-standard pupillometers, enabling reliable pupillary light reflex (PLR) analysis.

Distinguish neurological or mild traumatic brain injury cases from healthy controls with over 90% accuracy using machine learning on PLR curve features.

These findings demonstrate that smartphone pupillometry is increasingly recognised as a legitimate, objective, and scalable tool for autonomic and neurological assessment.

What’s New: Automated Collarette Analysis in PupilMetrics

Against this backdrop, certain apps extend classic pupillometry into iris morphology by adding automated collarette (ANW) analysis. The goal is to translate sector correlations into structured, reproducible data using everyday devices.

Key capabilities include:

Collarette shifts (drawing out / protrusion)

The system detects directional bulging by iris sector and labels shifts such as “middle-temporal” or “lower-temporal,” which can then be interpreted in light of cardiovascular and autonomic correlations.

Collarette constrictions (drawing in / narrowing)

It identifies frontal, basal, or combined frontal–basal constrictions and can simultaneously detect shift plus constriction in the same eye, reflecting complex autonomic patterns.

Machine-learning–assisted classification

Internal testing indicates that the algorithm correctly identifies the majority of pathological constriction patterns, with initial accuracy in the high 70% range, providing a strong baseline for future refinement.

Dual-pattern reporting

When both protrusion and constriction are present, the system reports them concurrently, capturing the nuanced “push–pull” behaviour of the collarette as an autonomic structure.

These features move iridology from purely descriptive language (“drawn in,” “spastic”) towards quantifiable, machine-readable pattern recognition.

Structured Outputs: ANW Ratio, Form Type, and Sectoral Asymmetry

To make collarette findings practical for clinicians and researchers, some apps generate structured, standardised output parameters:

ANW Ratio:

Reports the relative size and positioning of the collarette, with typical healthy ranges quoted around 25–35%, giving a quantitative handle on “spastic” versus “atonic” presentations.

ANW Form Type:

Classifies the wreath as Regular, Drawn In, or Drawn Out, corresponding to classic iridological descriptions of autonomic tone.

Zone Constrictions:

Provides text-based descriptions such as “Frontal zone constricted” or “Basal zone constricted” for rapid interpretation and documentation.

Sector-Based Asymmetry (%):

Quantifies left–right and sector-to-sector differences, labelling values as normal or pathological based on internal reference ranges.

Pattern Correlation:

Cross-compares pupillary metrics with ANW findings by sector, representing one of the first attempts to correlate PLR data and collarette morphology at a structured, algorithmic level.

For iridologists, this makes classical observations searchable, comparable over time, and suitable for case series, audits, and formal research.

Technical Enhancements: Standardisation, Analysis, and Device Support

For robust use in both clinics and studies, several technical issues have been addressed:

Standardisation of image acquisition distance

Variability in eye–camera distance can create false anisocoria or mis-scale collarette measurements. Some apps can estimate the acquisition distance in the right eye, then dynamically crops and scales the left eye image to match, ensuring consistent bilateral comparison.

Integrated pupillary light reflex (PLR) analysis

The apps can provides quantitative PLR metrics, aligning with published work showing that smartphone PLR can match dedicated pupillometers in precision and clinical utility.

Clinical and Research Implications for Iridologists

For practising iridologists and integrative clinicians, automated collarette analysis offers several concrete opportunities:

More objective autonomic profiling:

Quantified ANW ratios, asymmetries, and sector shifts can support or challenge subjective impressions, improving consistency between practitioners.

Longitudinal tracking:

Iris and PLR data can be monitored over time alongside interventions targeting cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, or stress-related conditions.

Cross-disciplinary collaboration:

Structured pupillometry and collarette metrics are more “research-ready,” enabling collaboration with neurologists, cardiologists, and digital health researchers interested in non-invasive autonomic markers.

Importantly, these tools are not intended to replace established diagnostic methods but to complement them—offering an additional layer of autonomic and morphologic information that can inform holistic assessment and lifestyle-focused care.

Ethical and Practical Considerations

As iridology moves into the digital, AI-assisted era, several considerations are essential:

Data privacy and consent:

Pupil and iris images are biometric identifiers; informed consent and secure storage are non-negotiable.

Scope-of-practice clarity:

Findings should be framed as functional, not as stand-alone medical diagnoses.

Avoiding overreach:

While early research is encouraging, correlative patterns do not equal causation. Collarette findings should be interpreted in context with clinical history, objective testing, and broader assessment.

Handled well, these considerations can help ensure that AI-enhanced iridology advances credibly and responsibly. It is also important to note that AI-based iris reading is solely intended to be used by registered professionals, and people should not use apps to self-diagnosed themselves.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Can I download a smartphone app to access PLR metrics?

Yes, you can. Although, some apps are only available on Androids, and many more are only available in certain countries.

Can a smartphone app replace a full iridology examination?

No. A smartphone-based system can standardise image capture, quantify collarette and PLR metrics, and highlight patterns, but it does not replace the nuance of a full case history, physical assessment, and clinical judgement. It should be viewed as a decision-support and documentation tool, not a stand-alone diagnostic system.

How reliable is smartphone pupillometry compared with dedicated devices?

Recent studies show strong agreement between well-designed smartphone pupillometry apps and commercial pupillometers, with high correlation in parameters such as pupil diameter and PLR dynamics. Accuracy depends on proper calibration, lighting control, and adherence to acquisition protocols.

Is automated collarette analysis scientifically validated?

Core components such as PLR measurement and artifact removal have been evaluated in peer-reviewed contexts, and the collarette algorithms are grounded in historical cardiovascular research and modern image processing. Large-scale validation specifically of collarette–disease correlations is an emerging area and represents a major opportunity for collaborative research.

References

Amiot, V. Tomasoni, M. Minier, A. et al. (2024). PupilMetrics: A support system for preprocessing of pupillometric data and extraction of outcome measures. Scientific Reports. 14(1), 28775. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-79920-z

Barry, C. De Souza, J. Xuan, Y. (2022). At-home pupillometry using smartphone facial identification cameras. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. 2022, 235. doi:10.1145/3491102.3502493

Clinical Neuro-Optic Reseach. (2026). The Collarette. Available at: Institute https://cnri.edu/the-collarette

Jaworski, D. Suwała, K. Kaluzny, BJ. (2025). Comparison of an AI-based mobile pupillometry system and NPi-200 for pupillary light reflex and correlation with glaucoma-related markers. Frontiers in Neurology. 15, 1426205. doi:10.3389/fneur.2024.1426205

Kim, KL. Kim, DK. Lee, JH. et al. (2025). SmartPLR: a digital solution for AI-powered smartphone pupillometry. BMC Ophthalmology. 25(1), 637. doi: 10.1186/s12886-025-04462-5

Kutum, C. Lakhe, P. (2025). Smartphone-based pupillometry in resource-limited settings: An 'eye-catching' prospect. Brain Spine. 5, 104384. doi:10.1016/j.bas.2025.104384

Laatikainen, L. Blach, RK. (1977). Behaviour of the iris vasculature in central retinal vein occlusion: a fluorescein angiographic study of the vascular response of the retina and the iris. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 61(4), pp. 272-7. doi:10.1136/bjo.61.4.272

Lim, YW. Park, YB. Park, YJ. (2016). A longitudinal study of iris parameters and their relationships with temperament characteristics. European Journal of Integrative Medicine. 8(6), pp. 991-1000. doi:10.1016/j.eujim.2016.09.006

McAnany, JJ. Smith, BM. Garland, A. et al. (2018). iPhone-based Pupillometry: A Novel Approach for Assessing the Pupillary Light Reflex. Optometry and Vision Science. 95(10), pp. 953-958. doi:10.1097/OPX.0000000000001289

Maxin, AJ. Lim, DH. Kush, S. et al. (2024). Smartphone pupillometry and machine learning for detection of acute mild traumatic brain injury: Cohort study. JMIR Neurotechnology. 3, e58398. doi:10.2196/58398

Sanchez, O. (2026). The Collarette. Available:

Schmidt, JC. Middleton, PM. Davies, W. (2025). A novel pupillometer smartphone application demonstrates accurate results compared with a validated clinical pupillometer: The Pupillary Light Response Validation (PLR-V) Study. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care. doi:10.1177/0310057X251381378

Song, Y. Song, YJ. Ko, MK. et al. (2009). A study of the vascular network of the iris using flat preparation. Korean Journal of Ophthalmology. 23(4), pp. 296-300. doi:10.3341/kjo.2009.23.4.296